A unity build can cut down build times dramatically and is HIGHLY underrated and easily dismissed by many senior software engineers (just like precompiled headers). In this post we will go over what it is, all its pros and cons, and why a “dirty hack” might be worth it if it speeds up your builds by at least a factor of 2 or perhaps even in the double-digits.

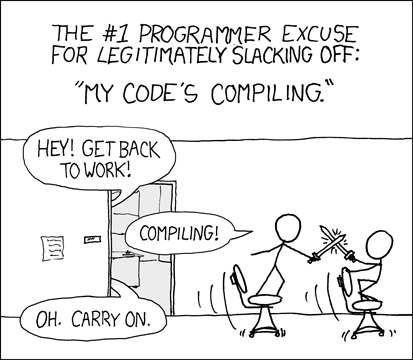

Why care about build times in the first place

Well… time is money! Let’s do the math: assuming an annual salary of 80k $ - waiting for 30 minutes extra a day for builds is 1/16 of the time of a developer ===> 5k $ per year. 200 such employees and we reach 1 million $ annually. But employees bring more value to the company than what they get as a salary (usually atleast x3 - if the company is adequate) - so the costs to the employer are actually bigger.

Now let’s consider the facts that waiting for long builds discourages refactoring and experimentation and leads to mental context switches + distractions which are always expensive - so we reach the only possible conclusion: any time spent reducing build times is worthwhile!

Introduction - a short summary to unity builds

A unity build is when a bunch of source files are #include‘d into a single file which is then compiled:

// unity_file.cpp

#include "widget.cpp"

#include "gui.cpp"

#include "test.cpp"

Also known as: SCU (single compilation unit), amalgamated or jumbo.

The main benefit is lower build times (compile + link) because:

- Commonly included headers get parsed/compiled only once.

- Less reinstantiation of the same templates: like

std::vector<int>. - Less work for the linker (for example not having to remove N-1 copies of the same weak symbol - an inline function defined in a header and included in N source files).

- less compiler invocations.

Note that we don’t have to include all sources in one unity file - as an example: 80 source files can be split in 8 unity files with 10 of the original sources included in each of them and then they can be built in parallel on 8 cores.

Why redundant header parsing/compilation is slow:

Here is what happens after including a single header with 2 popular compilers and running only the preprocessor (in terms of file size and lines of code):

| header | GCC 7 size | GCC 7 loc | MSVC 2017 size | MSVC 2017 loc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cstdlib | 43 kb | 1k loc | 158 kb | 11k loc |

| cstdio | 60 kb | 1k loc | 251 kb | 12k loc |

| iosfwd | 80 kb | 1.7k loc | 482 kb | 23k loc |

| chrono | 180 kb | 6k loc | 700 kb | 31k loc |

| variant | 282 kb | 10k loc | 1.1 mb | 43k loc |

| vector | 320 kb | 13k loc | 950 kb | 45k loc |

| algorithm | 446 kb | 16k loc | 880 kb | 41k loc |

| string | 500 kb | 17k loc | 1.1 mb | 52k loc |

| optional | 660 kb | 22k loc | 967 kb | 37k loc |

| tuple | 700 kb | 23k loc | 857 kb | 33k loc |

| map | 700 kb | 24k loc | 980 kb | 46k loc |

| iostream | 750 kb | 26k loc | 1.1 mb | 52k loc |

| memory | 760 kb | 26k loc | 857 kb | 40k loc |

| random | 1.1 mb | 37k loc | 1.4 mb | 67k loc |

| functional | 1.2 mb | 42k loc | 1.4 mb | 58k loc |

| all of them | 2.2 mb | 80k loc | 2.1 mb | 88k loc |

And here are some (common) headers from Boost (version 1.66):

| header | GCC 7 size | GCC 7 loc | MSVC 2017 size | MSVC 2017 loc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hana | 857 kb | 24k loc | 1.5 mb | 69k loc |

| optional | 1.6 mb | 50k loc | 2.2 mb | 90k loc |

| variant | 2 mb | 65k loc | 2.5 mb | 124k loc |

| function | 2 mb | 68k loc | 2.6 mb | 118k loc |

| format | 2.3 mb | 75k loc | 3.2 mb | 158k loc |

| signals2 | 3.7 mb | 120k loc | 4.7 mb | 250k loc |

| thread | 5.8 mb | 188k loc | 4.8 mb | 304k loc |

| asio | 5.9 mb | 194k loc | 7.6 mb | 513k loc |

| wave | 6.5 mb | 213k loc | 6.7 mb | 454k loc |

| spirit | 6.6 mb | 207k loc | 7.8 mb | 563k loc |

| geometry | 9.6 mb | 295k loc | 9.8 mb | 448k loc |

| all of them | 18 mb | 560k loc | 16 mb | 975k loc |

The point here is not to discredit Boost - this is an issue with the language itself when building zero-cost abstractions.

So if we have a few 5 kb source files with a 100 lines of code in each (because we write modular code) and we include some of these - we can easily get hundreds of thousands of lines of code (reaching megabyte sizes) for the compiler to go through for each source file of our tiny program. If some headers are commonly included in those source files then by employing the unity build technique we will compile the contents of each header just once - and this is where the biggest gains from unity builds come from.

A common misconception is that unity builds offer gains because of the reduced disk I/O - after the first time a header is read it is cached by the filesystem (they cache very aggressively since a cache miss is a huge hit).

The PROS of unity builds:

- Up to 90+% faster (depends on modularity - stitching a few 10k loc files together wouldn’t be much beneficial) - the best gains are with short sources and lots of (heavy) includes.

- Same as LTO (link-time optimizations - also LTCG) but even faster than normal full builds! Usually LTO builds take tremendously more time (but there are great improvements in that area such as clang’s ThinLTO).

- ODR (One Definition Rule) violations get caught (see this) - there are still no reliable tools for that. Example - the following code will result in a runtime bug since the linker will randomly remove one of the 2 methods and use the other one since they seem to be identical:

// a.cpp struct Foo { int method() { return 42; } // implicitly inline };// b.cpp struct Foo { int method() { return 666; } // implicitly inline }; - Enforces code hygiene such as include guards (or

#pragma once) in headers

The CONS:

- Not all valid C++ continues to compile:

- Clashes of symbols with identical names and internal linkage (in anonymous namespaces or static)

// a.cpp namespace { int local; }// b.cpp static int local; - Overload ambiguities (also non-explicit 1 argument constructor…?)

- Using namespaces in sources can be a problem

- Leaked preprocessor identifiers after some source which defines them

- Clashes of symbols with identical names and internal linkage (in anonymous namespaces or static)

- Might slow down some workflows:

- Minimal rebuilds - but if a source file can be excluded from the unity ones for faster iteration it should all be OK

- Might interfere with parallel compilation - but that can be tuned by better grouping of the sources to avoid “long poles” in compilation

- Might need a lot of RAM depending on how many sources you combine.

- One scary caveat is a miscompilation - when the program compiles successfully but in a wrong way (perhaps a better matching overload got chosen somewhere - or something to do with the preprocessor). Example:

// a.cpp struct MyStruct { MyStruct(int arg) : data(arg) {} int data; }; int func(MyStruct arg) { return arg.data; } int main() { return func(42); }// b.cpp int func(int arg) { return arg * 2; }If

b.cppends up beforea.cppthen we would get 84 instead of 42. However I haven’t seen this mentioned anywhere - people don’t run that much into it. Also good tests will definitely help.

How to maintain

We can manually maintain a set of unity source files - or automate that:

- CMake: either cotire or this

- FASTBuild

- Meson

- waf

- qmake

- Visual Studio Native Support

- Visual Studio Plugin

It is desirable to have control on:

- how many unity source files there are

- the order of source files in the unity files

- the ability to exclude certain files (if problematic or for iterating over them)

Projects using this technique

Unity builds are used in Ubisoft for almost 14 years! Also WebKit! And Unreal…

There are also efforts by people who build chrome often (and have gotten very good results - parts of it get built in 30% of the original time) to bring native support for unity builds into clang to minimize the code changes needed for the technique (gives unique names to objects with internal linkage (static or in anonymous namespaces), undefines macros between source files, etc.):

Leave a Comment